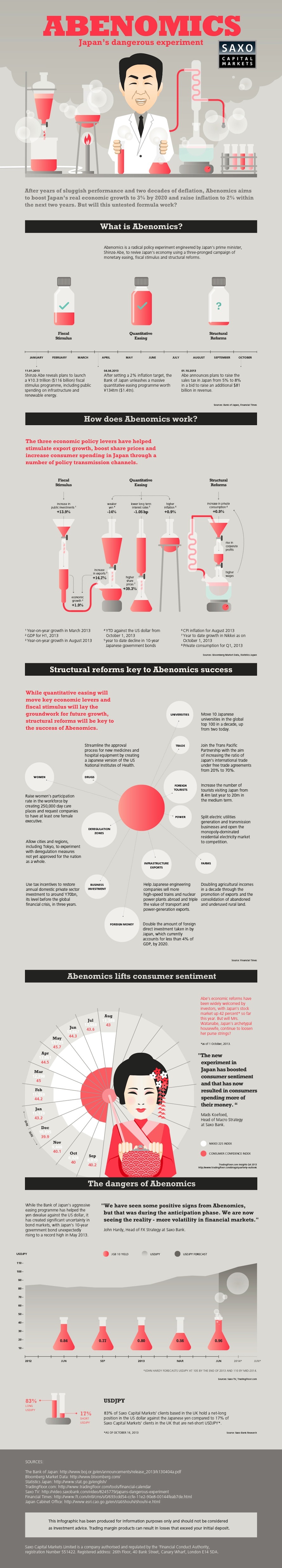

Abenomics: Japan’s Dangerous Experiment

Shinzō Abe, Japan’s prime minister, set out in early 2013 to rejuvenate Japan’s struggling economy with a $116 billion stimulus package, structural reforms, and $1.4 trillion of very loose monetary easing. In anticipation of the effects, Japan’s stock market surged. By May 2013, the stock market had risen by 55%, but these early indications turned out to be premature. Up until this point, it seems that Abenomics has not done much for the real growth of Japan’s economy, despite temporary boosts that were a consequence of optimism. As Bloomberg columnist, William Pesek, puts it, “so far, Abenomics has meant lots of stimulus and no deregulation, a recipe that has boosted inflation more than growth or confidence.” Another problem: the Japanese economy shrank by 6.8% during Q2 on an annualized basis. This was the direct result of a drop in consumer spending (~5% drop), brought on by an increase in sales tax. Japanese consumers scrambled to buy and hoard in Q1, before the new tax kicked in and cost of acquisition rose by 3%. Abenomics has so far been a disappointment. The world’s eyes are on Japan and we’re rooting for them. After all, the nation is the world’s third largest economy and global economics is an interdependent ecosystem. Original infographic from: UK Saxo Markets on Last year, stock and bond returns tumbled after the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest speed in 40 years. It was the first time in decades that both asset classes posted negative annual investment returns in tandem. Over four decades, this has happened 2.4% of the time across any 12-month rolling period. To look at how various stock and bond asset allocations have performed over history—and their broader correlations—the above graphic charts their best, worst, and average returns, using data from Vanguard.

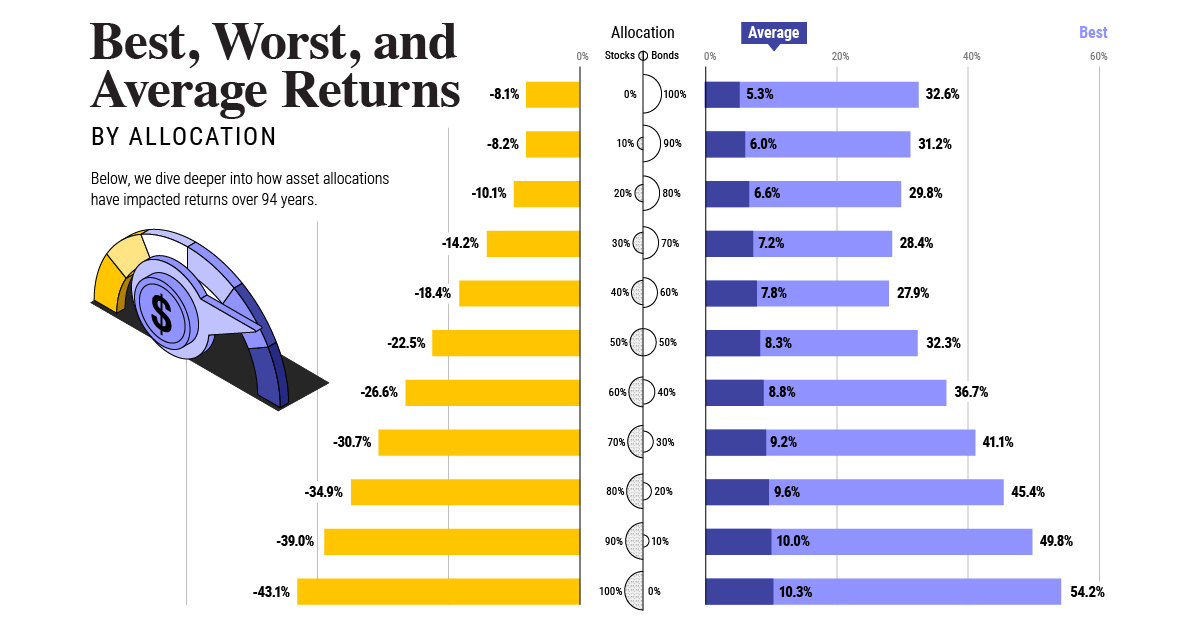

How Has Asset Allocation Impacted Returns?

Based on data between 1926 and 2019, the table below looks at the spectrum of market returns of different asset allocations:

We can see that a portfolio made entirely of stocks returned 10.3% on average, the highest across all asset allocations. Of course, this came with wider return variance, hitting an annual low of -43% and a high of 54%.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio—which has lost its luster in recent years as low interest rates have led to lower bond returns—saw an average historical return of 8.8%. As interest rates have climbed in recent years, this may widen its appeal once again as bond returns may rise.

Meanwhile, a 100% bond portfolio averaged 5.3% in annual returns over the period. Bonds typically serve as a hedge against portfolio losses thanks to their typically negative historical correlation to stocks.

A Closer Look at Historical Correlations

To understand how 2022 was an outlier in terms of asset correlations we can look at the graphic below:

The last time stocks and bonds moved together in a negative direction was in 1969. At the time, inflation was accelerating and the Fed was hiking interest rates to cool rising costs. In fact, historically, when inflation surges, stocks and bonds have often moved in similar directions. Underscoring this divergence is real interest rate volatility. When real interest rates are a driving force in the market, as we have seen in the last year, it hurts both stock and bond returns. This is because higher interest rates can reduce the future cash flows of these investments. Adding another layer is the level of risk appetite among investors. When the economic outlook is uncertain and interest rate volatility is high, investors are more likely to take risk off their portfolios and demand higher returns for taking on higher risk. This can push down equity and bond prices. On the other hand, if the economic outlook is positive, investors may be willing to take on more risk, in turn potentially boosting equity prices.

Current Investment Returns in Context

Today, financial markets are seeing sharp swings as the ripple effects of higher interest rates are sinking in. For investors, historical data provides insight on long-term asset allocation trends. Over the last century, cycles of high interest rates have come and gone. Both equity and bond investment returns have been resilient for investors who stay the course.