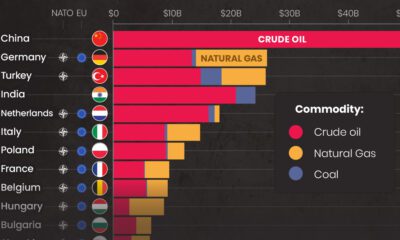

Oil is by far the world’s most-traded commodity, with $786.3 billion of crude changing hands in international trade in 2015. While low commodity prices can hurt any major producer, oil prices can have a particularly detrimental effect on oil-rich economies. This is because, for better or worse, many of these economies hold onto oil as an anchor for achieving growth, filling government coffers, and even fueling social programs. If those revenues don’t materialize as planned, these countries turn increasingly fragile. In the worst case scenario, an extended period of low oil prices can cause the fate of an entire regime to hang by a thread.

Which Countries are Damaged Most by Low Oil Prices?

This week’s chart explores three key pieces of high-level data on the oil sector from 2015: the cost of production ($/bbl), total oil production (MMbbl/day), and the world’s top exporters of oil ($). The general effects of these factors are pretty straightforward:

Countries that have a high cost of production per barrel are going to find it tough to make money in a low oil price environment Countries that are major producers or exporters tend to rely on oil revenues as a major economic driver Oil producers that are major exporters also have to deal with another factor: the effect that low oil prices may have on their currencies

Here are some particular countries that are under duress from current energy prices: Venezuela Back in the Hugo Chávez era, things were better in Venezuela than they are today. Oil prices were mostly sky-high, and this enabled the socialist country to bring down inequality as well as put food on the table for its citizens. However, as the World Bank described in 2012, since oil accounted for “96% of the country’s exports and nearly half of its fiscal revenue”, Venezuela was left “extremely vulnerable” to changes in oil prices. And change they did. Oil prices are now less than 50% of what they were when the World Bank wrote the above commentary. Partially as a result, Venezuela is having all sorts of problems, ranging from runaway hyperinflation to shortages in almost everything. Venezuela’s cost per barrel isn’t bad at $23.50, but the country is the world’s ninth-largest oil exporter with $27.8 billion of exports in 2015. If oil prices were north of $100/bbl, Venezuela’s situation would be a lot less dire. Russia Russia is the world’s second-largest crude oil exporter, shipping $86.2 billion to countries outside of its borders in 2015. That’s good for 11.0% of all oil exports globally. Russia’s cost of production in 2015 was relatively low, at $17.30 per barrel. But is declining oil revenue influencing foreign policy? It’s hard to say – but we do know that, historically, leaders have turned to nationalist projects during tougher economic times. In this case, Putin may have focused Russia’s national attention on Ukraine as a way to deflect from a less-than-rosy economic outlook. Brazil All is not well in Brazil, where President Dilma Rousseff could be impeached by as early as next week. Brazil is the ninth-largest producer of oil globally, pumping out about 3.2 million barrels per day. However, a bigger concern may be the cost of producing oil in the country. The production cost in 2015 was a hefty $48.80/bbl, among the most expensive of major oil producers. The post-Olympics hangover will be a challenging one in Brazil, as it faces its worst economic crisis in 30 years. The largest country in Latin America had its economy shrink 5.4% in the first quarter of this year. Nigeria Nigeria, which will soon be one of the three most populous countries in the world, is also very reliant on oil revenues to prop up its economy. The country has a $7 billion budget deficit due to lower oil revenues, and it recently also dropped its peg to the U.S. dollar on June 15th. The naira fell 61% against the dollar since then, wreaking havoc throughout the economy. Nigeria also recently lost its title of “Africa’s largest economy”, handing it back to South Africa. Nigeria is the sixth-largest exporter of oil, with annual exports of $38 billion in 2015. Its cost of production is higher than average, as well, at $31.50 per barrel. Canada Canada’s economy is largely diversified, but it is also the world’s fifth-largest exporter of oil with $50.2 billion of exports in 2015. Costs are also high in the oil sands, and the average cost of production per barrel was $41.10 throughout the country. The oil bust has dragged the energy-rich province of Alberta into a recession, and the Canadian dollar is also severely impacted by oil prices for multiple reasons. Alberta’s economy is about to have its largest two-year contraction on record, while the provincial government’s deficit has exploded to $10.9 billion. Energy investment in Alberta is forecast to be about half of the total from 2014. Meanwhile, economic conditions elsewhere have also been impacted, as areas such as housing, retail, labor markets, and manufacturing have all felt the pinch. on Last year, stock and bond returns tumbled after the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest speed in 40 years. It was the first time in decades that both asset classes posted negative annual investment returns in tandem. Over four decades, this has happened 2.4% of the time across any 12-month rolling period. To look at how various stock and bond asset allocations have performed over history—and their broader correlations—the above graphic charts their best, worst, and average returns, using data from Vanguard.

How Has Asset Allocation Impacted Returns?

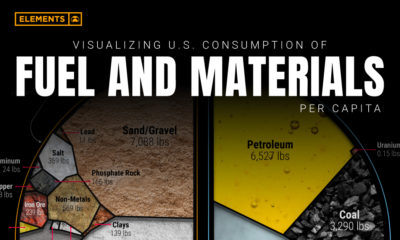

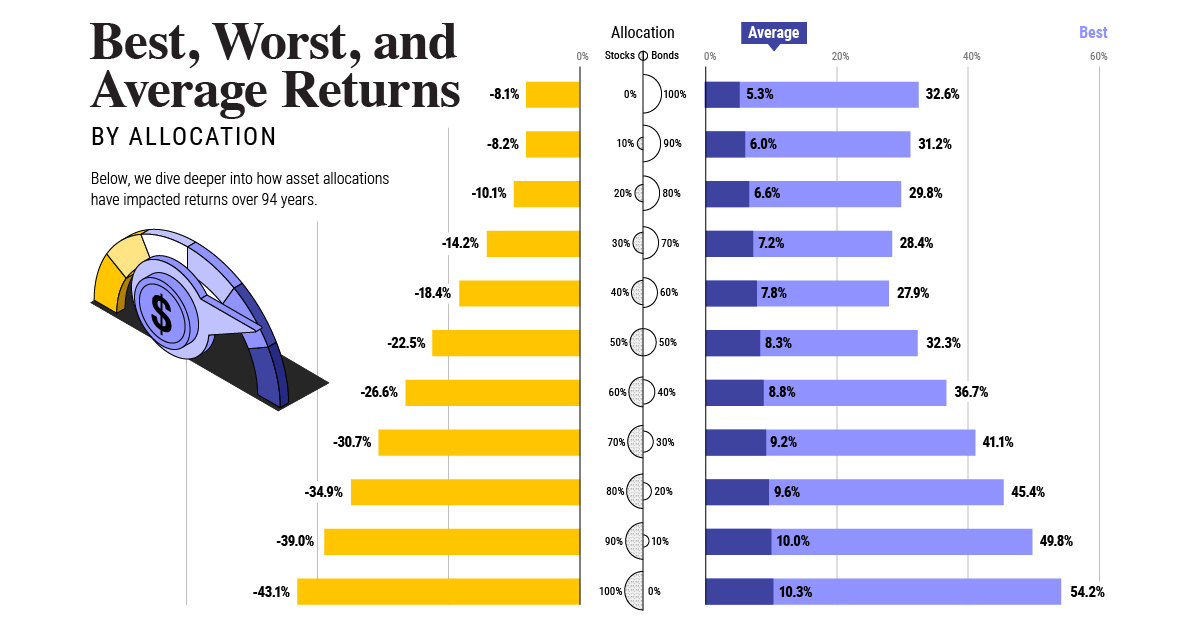

Based on data between 1926 and 2019, the table below looks at the spectrum of market returns of different asset allocations:

We can see that a portfolio made entirely of stocks returned 10.3% on average, the highest across all asset allocations. Of course, this came with wider return variance, hitting an annual low of -43% and a high of 54%.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio—which has lost its luster in recent years as low interest rates have led to lower bond returns—saw an average historical return of 8.8%. As interest rates have climbed in recent years, this may widen its appeal once again as bond returns may rise.

Meanwhile, a 100% bond portfolio averaged 5.3% in annual returns over the period. Bonds typically serve as a hedge against portfolio losses thanks to their typically negative historical correlation to stocks.

A Closer Look at Historical Correlations

To understand how 2022 was an outlier in terms of asset correlations we can look at the graphic below:

The last time stocks and bonds moved together in a negative direction was in 1969. At the time, inflation was accelerating and the Fed was hiking interest rates to cool rising costs. In fact, historically, when inflation surges, stocks and bonds have often moved in similar directions. Underscoring this divergence is real interest rate volatility. When real interest rates are a driving force in the market, as we have seen in the last year, it hurts both stock and bond returns. This is because higher interest rates can reduce the future cash flows of these investments. Adding another layer is the level of risk appetite among investors. When the economic outlook is uncertain and interest rate volatility is high, investors are more likely to take risk off their portfolios and demand higher returns for taking on higher risk. This can push down equity and bond prices. On the other hand, if the economic outlook is positive, investors may be willing to take on more risk, in turn potentially boosting equity prices.

Current Investment Returns in Context

Today, financial markets are seeing sharp swings as the ripple effects of higher interest rates are sinking in. For investors, historical data provides insight on long-term asset allocation trends. Over the last century, cycles of high interest rates have come and gone. Both equity and bond investment returns have been resilient for investors who stay the course.