That said, many jurisdictions have experienced serious delays and supply shortages that have made it difficult to distribute COVID-19 vaccine doses to their populations. As of mid-February, 130 countries had not been able to begin vaccinating at all. This interactive chart from Our World in Data tracks the share of people in each country that have received COVID-19 vaccine doses so far.

The Global Vaccine Rollout

As of publication date, roughly 100 countries have begun vaccine distribution, with about seven different vaccines available for public use at this stage. The sheer logistical challenge of doling out vaccines is immense. Experts estimate that 70-80% of the world’s population will need to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity. Additionally, some of the vaccines require two doses which adds extra time and complexity to the process. Here’s how the various vaccines compare in terms of required doses and levels of effectiveness. Source: Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker One key barrier to successfully administering vaccines is the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy around the globe. For example, many people in Germany have been refusing the AstraZeneca vaccine due to a belief in its ineffectiveness and a preference for the ‘in-house’ German Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Although 1.45 million AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine doses have arrived in the country so far, just 270,000 have been administered.

Who’s Got at Least One Dose?

According to Bloomberg’s Vaccine Tracker, the current rate of doses being administered globally is more than 6 million per day. In particular, the U.S. has been remarkably efficient at administering doses, with a vaccine administration rate of over 1.7 million per day. Here’s a breakdown of the countries who have begun vaccinating their populations and their current daily rate of doses administered. Source: Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker. Data as of Feb 28, 2021. Certain countries appear to be on track to distribute all of their COVID-19 vaccine doses at an immensely quick rate. For example, the UK plans to vaccinate enough people to be able to lift all lockdown restrictions completely by the end of June 2021. Additionally, the first COVAX rollouts have officially begun; COVAX is an initiative working to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. Ghana was the first country to receive doses through the initiative.

Back to Normal?

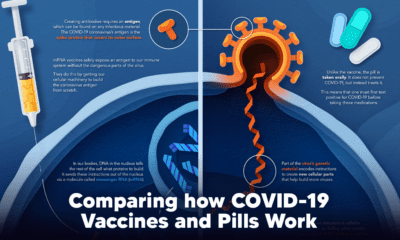

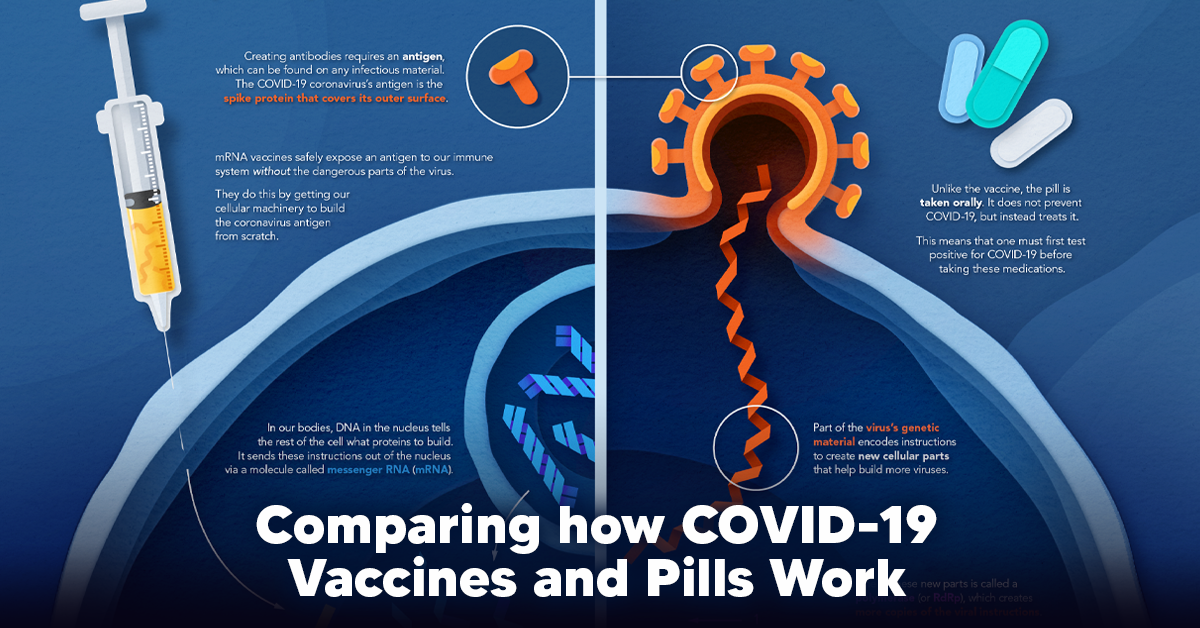

Most countries are prioritizing vaccinating their high-risk groups first, from older adults to healthcare workers. That said, the planning required to vaccinate an entire population needs to be carefully thought out and often comes with immense logistical challenges. While many countries have begun to immunize their populations, others have not been able to purchase doses yet. At the current pace, it could take a few years before things are completely back to normal and we reach herd immunity globally. on The leading options for preventing infection include social distancing, mask-wearing, and vaccination. They are still recommended during the upsurge of the coronavirus’s latest mutation, the Omicron variant. But in December 2021, The United States Food and Drug Administration (USDA) granted Emergency Use Authorization to two experimental pills for the treatment of new COVID-19 cases. These medications, one made by Pfizer and the other by Merck & Co., hope to contribute to the fight against the coronavirus and its variants. Alongside vaccinations, they may help to curb extreme cases of COVID-19 by reducing the need for hospitalization. Despite tackling the same disease, vaccines and pills work differently:

How a Vaccine Helps Prevent COVID-19

The main purpose of a vaccine is to prewarn the body of a potential COVID-19 infection by creating antibodies that target and destroy the coronavirus. In order to do this, the immune system needs an antigen. It’s difficult to do this risk-free since all antigens exist directly on a virus. Luckily, vaccines safely expose antigens to our immune systems without the dangerous parts of the virus. In the case of COVID-19, the coronavirus’s antigen is the spike protein that covers its outer surface. Vaccines inject antigen-building instructions* and use our own cellular machinery to build the coronavirus antigen from scratch. When exposed to the spike protein, the immune system begins to assemble antigen-specific antibodies. These antibodies wait for the opportunity to attack the real spike protein when a coronavirus enters the body. Since antibodies decrease over time, booster immunizations help to maintain a strong line of defense. *While different vaccine technologies exist, they all do a similar thing: introduce an antigen and build a stronger immune system.

How COVID Antiviral Pills Work

Antiviral pills, unlike vaccines, are not a preventative strategy. Instead, they treat an infected individual experiencing symptoms from the virus. Two drugs are now entering the market. Merck & Co.’s Lagevrio®, composed of one molecule, and Pfizer’s Paxlovid®, composed of two. These medications disrupt specific processes in the viral assembly line to choke the virus’s ability to replicate.

The Mechanism of Molnupiravir

RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) is a cellular component that works similar to a photocopying machine for the virus’s genetic instructions. An infected host cell is forced to produce RdRp, which starts generating more copies of the virus’s RNA. Molnupiravir, developed by Merck & Co., is a polymerase inhibitor. It inserts itself into the viral instructions that RdRp is copying, jumbling the contents. The RdRp then produces junk.

The Mechanism of Nirmatrelvir + Ritonavir

A replicating virus makes proteins necessary for its survival in a large, clumped mass called a polyprotein. A cellular component called a protease cuts a virus’s polyprotein into smaller, workable pieces. Pfizer’s antiviral medication is a protease inhibitor made of two pills: With a faulty polymerase or a large, unusable polyprotein, antiviral medications make it difficult for the coronavirus to replicate. If treated early enough, they can lessen the virus’s impact on the body.

The Future of COVID Antiviral Pills and Medications

Antiviral medications seem to have a bright future ahead of them. COVID-19 antivirals are based on early research done on coronaviruses from the 2002-04 SARS-CoV and the 2012 MERS-CoV outbreaks. Current breakthroughs in this technology may pave the way for better pharmaceuticals in the future. One half of Pfizer’s medication, ritonavir, currently treats many other viruses including HIV/AIDS. Gilead Science is currently developing oral derivatives of remdesivir, another polymerase inhibitor currently only offered to inpatients in the United States. More coronavirus antivirals are currently in the pipeline, offering a glimpse of control on the looming presence of COVID-19. Author’s Note: The medical information in this article is an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Please talk to your doctor before undergoing any treatment for COVID-19. If you become sick and believe you may have symptoms of COVID-19, please follow the CDC guidelines.