Historically, however, this hasn’t always been the case. Time travel back just 20 years ago to 2002, and you’d notice the vast majority of people were still waiting on the daily paper or the evening news to help fill the information void. In fact, for most of 2002, Google was trailing in search engine market share behind Yahoo! and MSN. Meanwhile, early social media incarnations (MySpace, Friendster, etc.) were just starting to come online, and all of Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and the iPhone did not yet exist.

The Waves of Media So Far

Every so often, the dominant form of communication is upended by new technological developments and changing societal preferences. These transitions seem to be happening faster over time, aligning with the accelerated progress of technology.

Proto-Media (50,000+ years) Humans could only spread their message through human activity. Speech, oral tradition, and manually written text were most common mediums to pass on a message. Analog and Early Digital Media (1430-2004) The invention of the printing press, and later the radio, television, and computer unlock powerful forms of one-way and cheap communication to the masses. Connected Media (2004-current) The birth of Web 2.0 and social media enables participation and content creation for everyone. One tweet, blog post, or TikTok video by anyone can go viral, reaching the whole world.

Each new wave of media comes with its own pros and cons. For example, Connected Media was a huge step forward in that it enabled everyone to be a part of the conversation. On the other hand, algorithms and the sheer amount of content to sift through has created a lot of downsides as well. To name just a few problems with media today: filter bubbles, sensationalism, clickbait, and so on. Before we dive into what we think is the next wave of media, let’s first break down the common attributes and problems with prior waves.

Wave Zero: Proto-Media

Before the first wave of media, amplifying a message took devotion and a lifetime. Add in the fact that even by the year 1500, only 4% of global citizens lived in cities, and you can see how hard it would be to communicate effectively with the masses during this era. Or, to paint a more vivid picture of what proto-media was like: information could only travel as fast as the speed of a horse.

Wave 1: Analog and Early Digital Media

In this first wave, new technological advancements enabled widescale communication for the first time in history. Newspapers, books, magazines, radios, televisions, movies, and early websites all fit within this framework, enabling the owners of these assets to broadcast their message at scale. With large amounts of infrastructure required to print books or broadcast television news programs, it took capital or connections to gain access. For this reason, large corporations and governments were usually the gatekeepers, and ordinary citizens had limited influence. Importantly, these mediums only allowed one-way communication—meaning that they could broadcast a message, but the general public was restricted in how they could respond (i.e. a letter to the editor, or a phone call to a radio station).

Wave 2: Connected Media

Innovations like Web 2.0 and social media changed the game. Starting in the mid-2000s, barriers to entry began to drop, and it eventually became free and easy for anyone to broadcast their opinion online. As the internet exploded with content, sorting through it became the number one problem to solve. For better or worse, algorithms began to feed people what they loved, so they could consume even more. The ripple effect of this was that everyone competing for eyeballs suddenly found themselves optimizing content to try and “win” the algorithm game to get virality. Viral content is often engaging and interesting, but it comes with tradeoffs. Content can be made artificially engaging by sensationalizing, using clickbait, or playing loose with the facts. It can be ultra-targeted to resonate emotionally within one particular filter bubble. It can be designed to enrage a certain group, and mobilize them towards action—even if it is extreme. Despite the many benefits of Connected Media, we are seeing more polarization than ever before in society. Groups of people can’t relate to each other or discuss issues, because they can’t even agree on basic facts. Perhaps most frustrating of all? Many people don’t know they are deep within their own bubble in which they are only fed information they agree with. They are unaware that other legitimate points of view exist. Everything is black and white, and grey thinking is rarer and rarer.

Wave 3: Data Media

Between 2015 and 2025, the amount of data captured, created, and replicated globally will increase by 1,600%. For the first time ever, a significant quantity of data is becoming “open source” and available to anyone. There have been massive advancements in how to store and verify data, and even the ownership of information can now be tracked on the blockchain. Both media and the population are becoming more data literate, and they are also becoming aware of the societal drawbacks stemming from Connected Media. As this new wave emerges, it’s worth examining some of its attributes and connecting concepts in more detail:

Transparency: Data literate users will begin to demand that data is transparent and originating from trustworthy, factual sources. Or if a source is not rock solid, users will demand that limitations of methodology or possible biases are openly revealed and discussed. Verifiability and Trust: How do we know data shown is legitimate and bonafide? Platforms and media will increasingly want to prove to users that data has been verified, going all the way back to the original source. Decentralization and Web3: Anyone can tap into large amounts of public data available today, which means that reporting, analysis, ideas, and insights can come from an increasingly growing set of actors. Web3 and decentralized ledgers will allow us to provide trust, attribution, accountability, and even ownership of content when necessary. This can remove the middleman, which is often large tech companies, and can allow users to monetize their content more directly. Data Storytelling Growing data literacy, and the explosion of data storytelling is a key approach to making sense of vast amounts of data, by combining data visualization, narrative, and powerful insights. Data Creator Economy: Democratized data and the rise of storytelling are intersecting to create a potential new ecosystem for data storytellers. This is increasingly what we are focused on at Visual Capitalist, and we encourage you to support our Kickstarter project on this (just 6 days left, as of publishing time) Open-Ended Ecosystem: Just like open source has revolutionized the software industry, we will begin to see more and more data available broadly. Incentives may shift in some cases from keeping data proprietary, to getting it out in the open so that others can use, remix, and publish it, and attributing it back to the original source. Data > Opinion: Data Media will have a bias towards facts over opinion. It’s less about punditry, bias, spin, and telling others what they should think, and more about allowing an increasingly data literate population to have access to the facts themselves, and to develop their own nuanced opinion on them. Global Data Standards: As data continues to proliferate, it will be important to codify and unify it when possible. This will lead to global standards that will make communicating it even easier.

Early Pioneers of Data Media

The Data Media ecosystem is just beginning to emerge, but here are some early pioneers we like:

Our World in Data: Led by economist Max Roser, OWiD is doing an excellent job amalgamating global economic data in one place, and making it easy for others to remix and communicate those insights effectively. USAFacts: Founded by Steve Ballmer of Microsoft fame to be a non-partisan source of U.S. government data. FRED: This tool by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis is just one example of many tools that have cropped up over the years to democratize data that were previously proprietary or hard to access. Other similar tools have been created by the IMF, World Bank, and so on. FiveThirtyEight: FiveThirtyEight uses statistical analysis, data journalism, and predictions to cover politics, sports, and other topics in a unique way. FlowingData: At FlowingData, data viz expert Nathan Yau explores a wide variety of data and visualization themes. Data Journalists: There are incredible data journalists at publications like The Economist, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Reuters that are tapping into the early beginnings of what is possible. Many of these publications also made their COVID-19 work freely available during the pandemic, which is certainly commendable.

Growth in data journalism and the emergence of these pioneers helps give you a sense of the beginnings of Data Media, but we believe they are only scratching the surface of what is possible.

What Data Media is Not

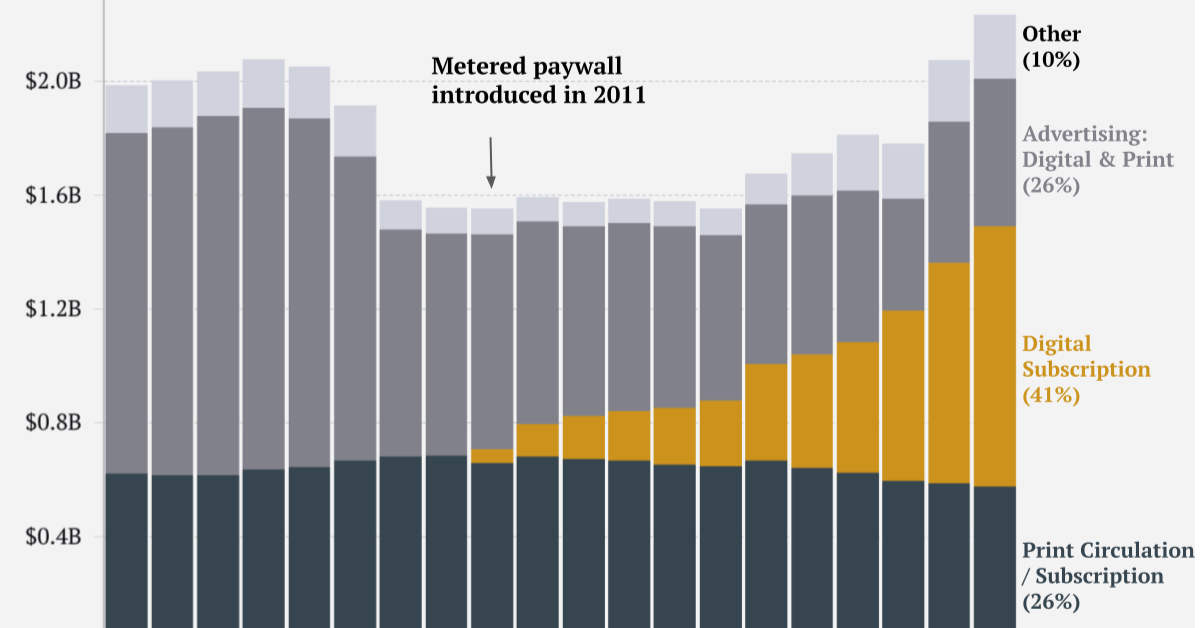

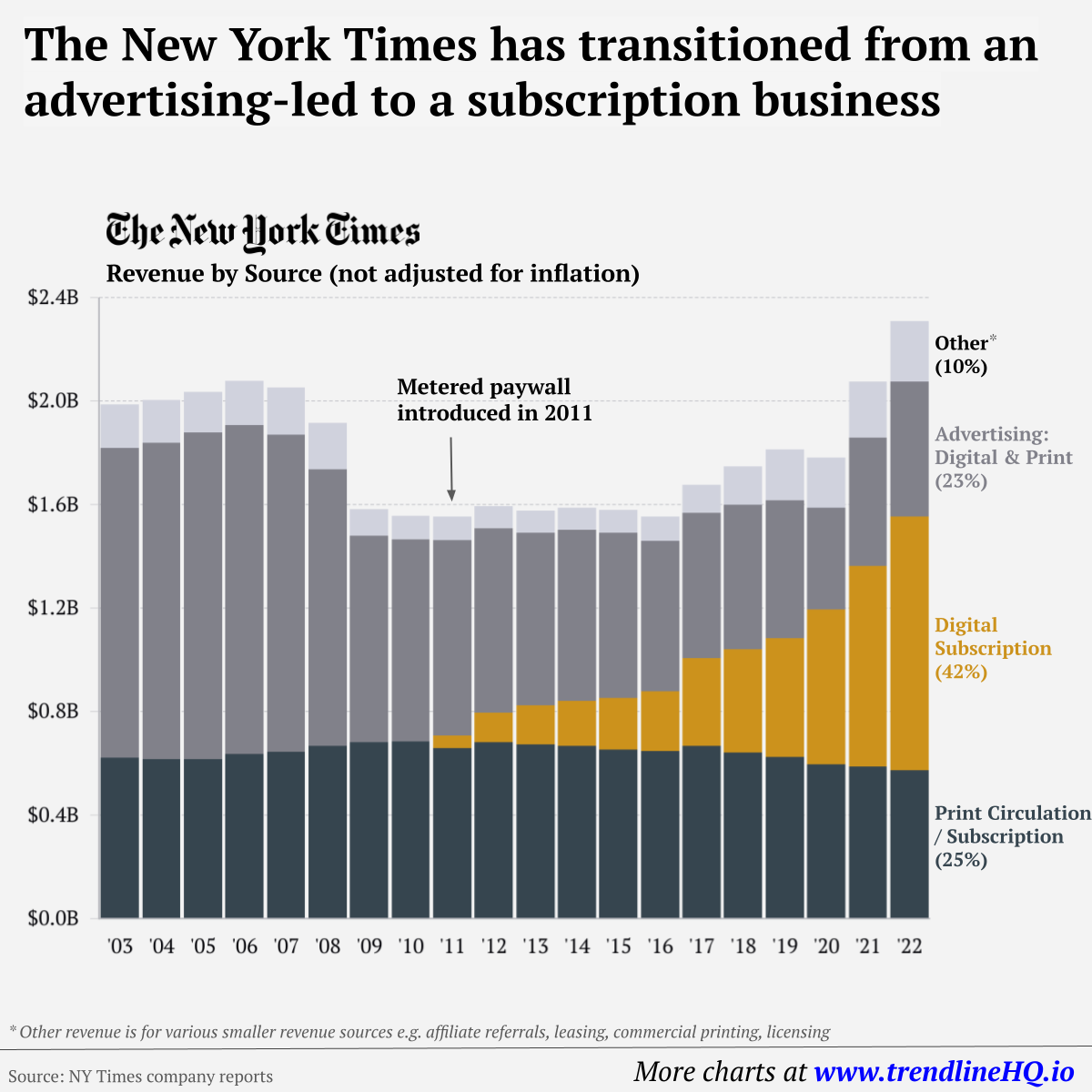

In a sense, it’s easier to define what Data Media isn’t. Data Media is not partisan pundits arguing over each other on a newscast, and it’s not fake news, misinformation, or clickbait that is engineered to drive easy clicks. Data media is not an echo chamber that only reinforces existing biases. Because data is also less subjective, it’s less likely to be censored in the way we see today. Data is not perfect, but it can help change the conversations we are having as a society to be more constructive and inclusive. We hope you agree! on Similar to the the precedent set by the music industry, many news outlets have also been figuring out how to transition into a paid digital monetization model. Over the past decade or so, The New York Times (NY Times)—one of the world’s most iconic and widely read news organizations—has been transforming its revenue model to fit this trend. This chart from creator Trendline uses annual reports from the The New York Times Company to visualize how this seemingly simple transition helped the organization adapt to the digital era.

The New York Times’ Revenue Transition

The NY Times has always been one of the world’s most-widely circulated papers. Before the launch of its digital subscription model, it earned half its revenue from print and online advertisements. The rest of its income came in through circulation and other avenues including licensing, referrals, commercial printing, events, and so on. But after annual revenues dropped by more than $500 million from 2006 to 2010, something had to change. In 2011, the NY Times launched its new digital subscription model and put some of its online articles behind a paywall. It bet that consumers would be willing to pay for quality content. And while it faced a rocky start, with revenue through print circulation and advertising slowly dwindling and some consumers frustrated that once-available content was now paywalled, its income through digital subscriptions began to climb. After digital subscription revenues first launched in 2011, they totaled to $47 million of revenue in their first year. By 2022 they had climbed to $979 million and accounted for 42% of total revenue.

Why Are Readers Paying for News?

More than half of U.S. adults subscribe to the news in some format. That (perhaps surprisingly) includes around four out of 10 adults under the age of 35. One of the main reasons cited for this was the consistency of publications in covering a variety of news topics. And given the NY Times’ popularity, it’s no surprise that it recently ranked as the most popular news subscription.