Every day, the Information Age bombards us with massive amounts of data. Experts now estimate that there are 40 times more bytes of data in existence than there are stars in the whole observable universe. And like the universe, our datasphere is also rapidly expanding—and every few years, there is actually more new data created than in all prior years of human history combined.

Searching for Signals

On a practical level, this dense wall of impenetrable data creates a multitude of challenges for investors and decision makers alike:

It’s mentally taxing to process all the available information out there Too much data can lead to “analysis paralysis”—an inability to make decisions Misinformation and media slant add another layer for our brains to process Our personal biases get reinforced by news algorithms and filter bubbles Data sources—even quality ones—can sometimes conflict with one another

As a result, it’s clear that people don’t want more data—they want more understanding. And for this reason, our team at Visual Capitalist has spent most of 2020 sifting through the noise to find the underlying trends that will transform society and markets over the coming years. The end result of this effort is our new hardcover book “SIGNALS: Charting the New Direction of the Global Economy” (hardcover, ebook) which beautifully illustrates 27 clear signals in fields ranging from investing to geopolitics.

The 6 Signals Shaping the Future of Finance

What clear and simple trends will shape the future of markets? Below, we show you a small selection of the hundreds of charts found in the book with a focus on global finance and investing:

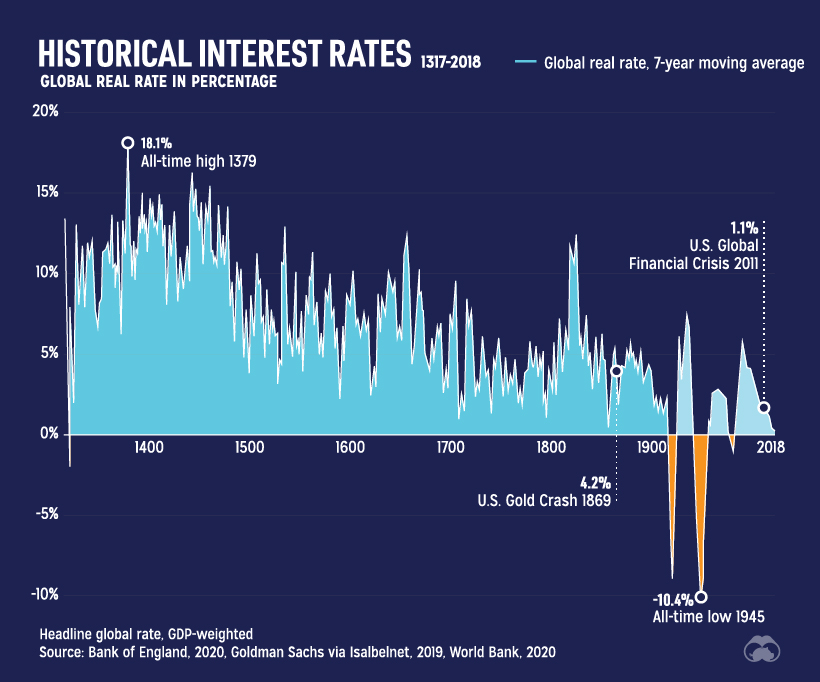

#1: 700 Years of Falling Interest Rates

The first signal we’ll showcase here is from an incredible dataset from the Bank of England, which reconstructs global real interest rates going back all the way to the 14th century.

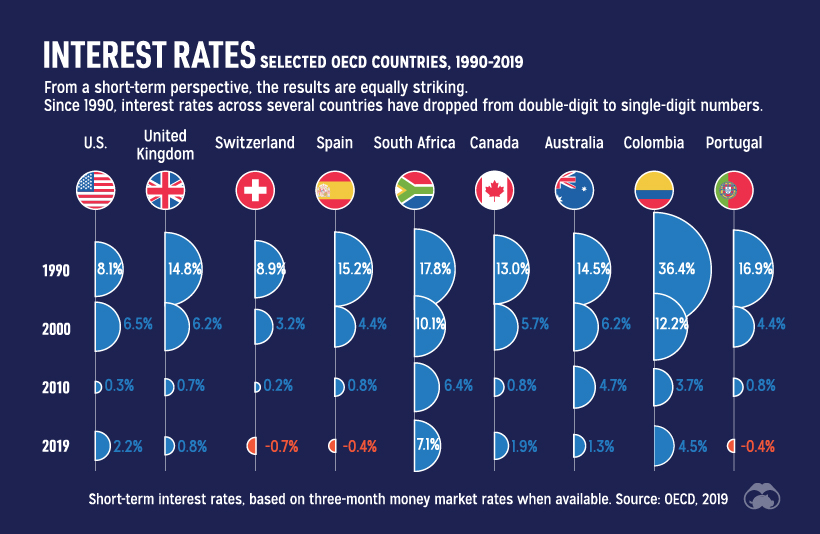

Some of the first data points in this series represent well-documented municipal debt issued in early Italian banking centers like Genoa, Florence, or Venice, during the beginning stages of the Italian Renaissance. The early data sets of loans to noblemen, merchants, and kingdoms eventually merge with more contemporary data from central banks, and over the centuries it’s clear that falling interest rates are not a new phenomenon. In fact, on average, real rates have decreased by 1.6 basis points (0.016%) per year since the 14th century. This same spectacle can also be seen in more modern time stretches:

And as the world reels from the COVID-19 crisis, governments are taking advantage of record-low rates to issue more debt and stimulate the economy. This brings us to our next signal.

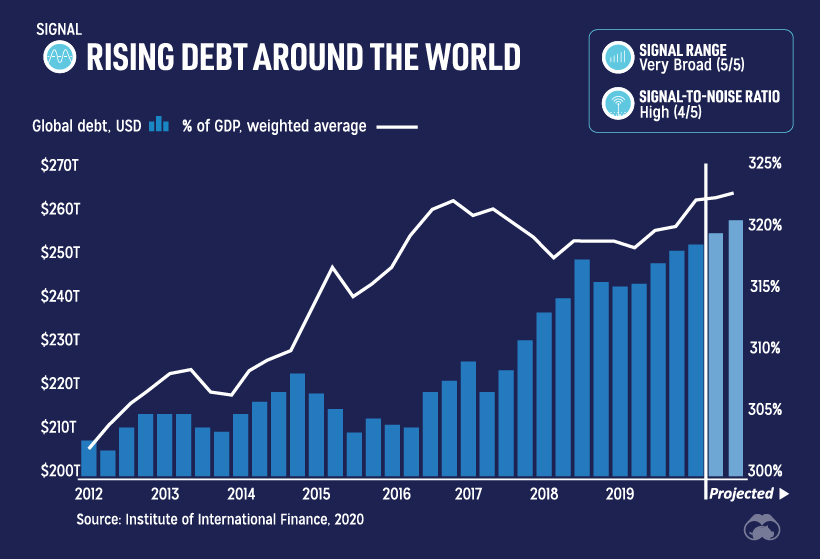

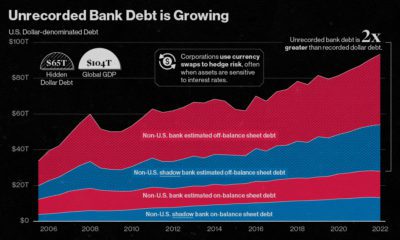

#2: Global Debt: To $258 Trillion and Beyond

The ongoing pandemic certainly made analysis trickier for some signals, but easier for others. The accumulation of global debt falls into the latter category: as of Q1 2020, global debt sits at a record $258 trillion or 331% of world GDP, and it’s projected to rise sharply as a result of fiscal stimulus, falling tax revenues, and increasing budget deficits.

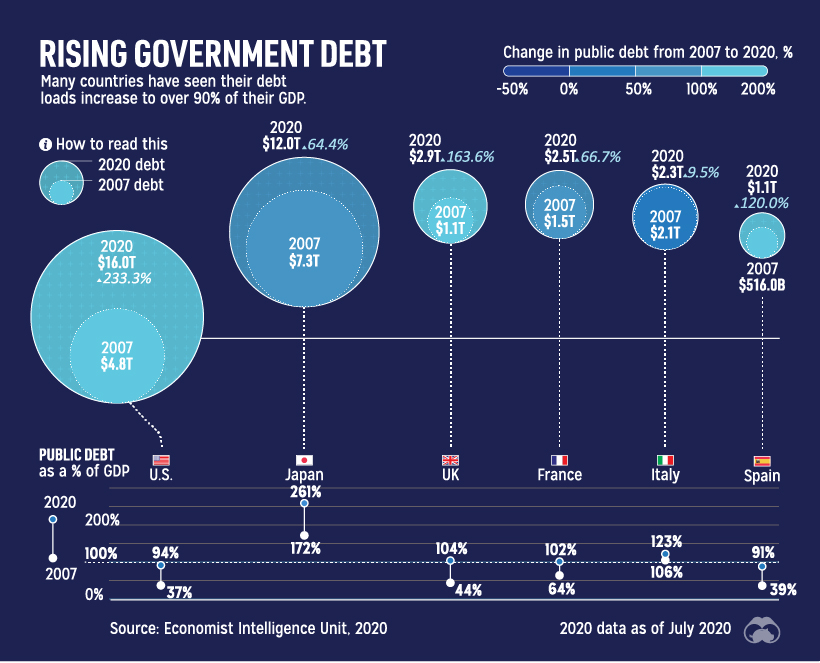

The above chart takes into consideration consumer, corporate, and government debt—but let’s just zoom in on government debt for a moment. The below data, which is from early 2020, shows government debt ballooning between 2007 and early 2020 as a percentage of GDP.

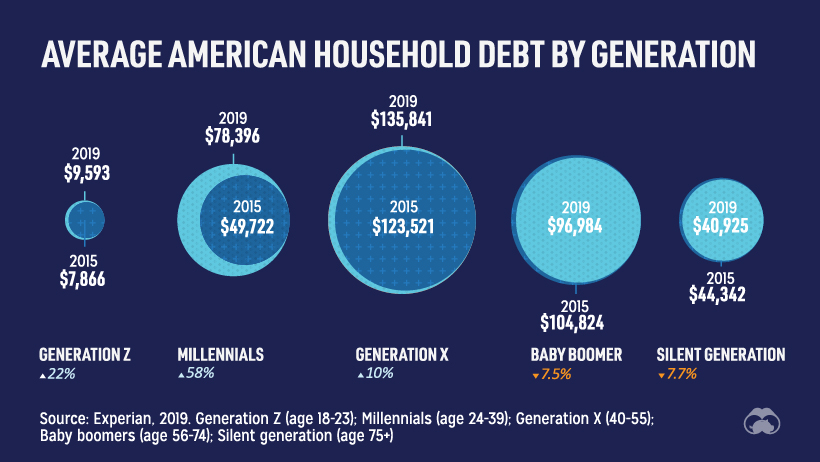

This chart does not include intragovernmental debt or new debt taken on after the start of the pandemic. Despite this, the percentage increase in debt held by some of these governments is in the triple digits over a period of only 13 years, including the 233% increase in the United States. But it’s not just governments going on a borrowing spree. The following chart shows consumer debt over a recent four-year span, sorted by generation:

While Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation are successfully winding down some of their debt, younger generations are just getting aboard the debt train. Between 2015-2019, Millennials added 58% to household debt, while Gen Xers find themselves (in the middle of their mortgage-paying years) as the most indebted generation with $135,841 of debt per household.

#3: Blue Chips and the Circle of Life

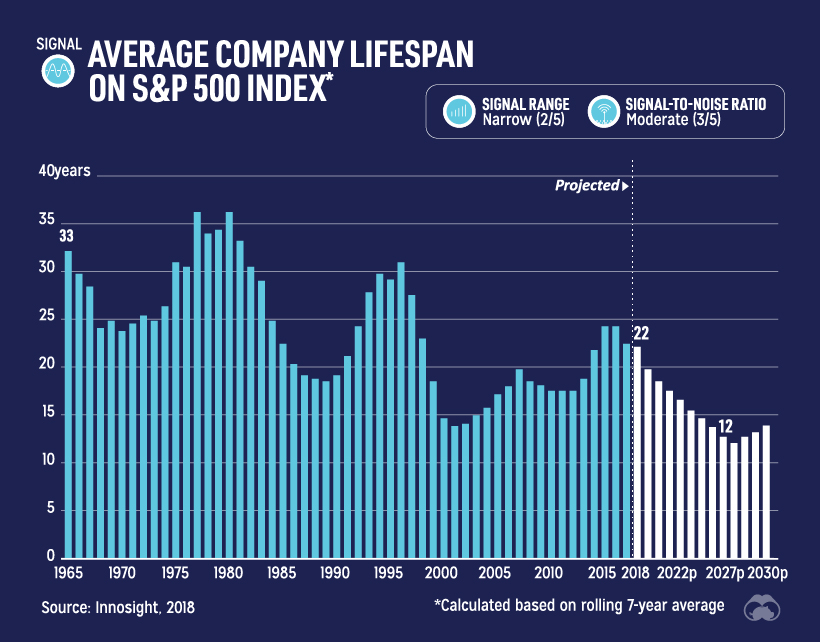

There was a time when it seemed absolutely unfathomable that large, entrenched companies could see their corporate advantages slide away. But as the recent collapses of Blockbuster, Lehman Brothers, Kodak, or various retailers have taught us, there are no longer any guarantees around corporate longevity.

In 1964, the average tenure of a company on the S&P 500 was 33 years, but this is projected to fall to an average of just 12 years by the year 2027 according to consulting firm Innosight. At this churn rate, it’s expected that 50% of the S&P 500 could turnover between 2018-2027.

For established companies, this is a sign of the times. Between the rapid acceleration in the speed of innovation and continuously falling barriers to market entry, the traditional corporate world finds itself playing defense. For investors and startups, this is an interesting prospect to consider, as disruption now appears to be the status quo. Could the next big company to dominate global markets be found in someone’s garage in India today? If you like this post, find hundreds of charts like this in our new book “Signals”:

#4: ESG is the New Status Quo

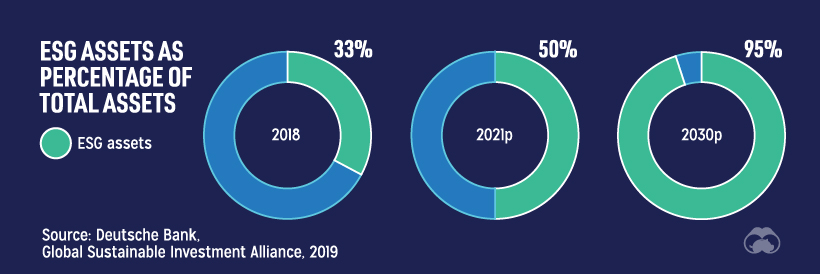

The investment universe has reached an interesting tipping point. Historically, performance was all the mattered to most investors—but going forward, considering ESG criteria (environment, social, and governance) is expected to become a default component of investment strategy as well.

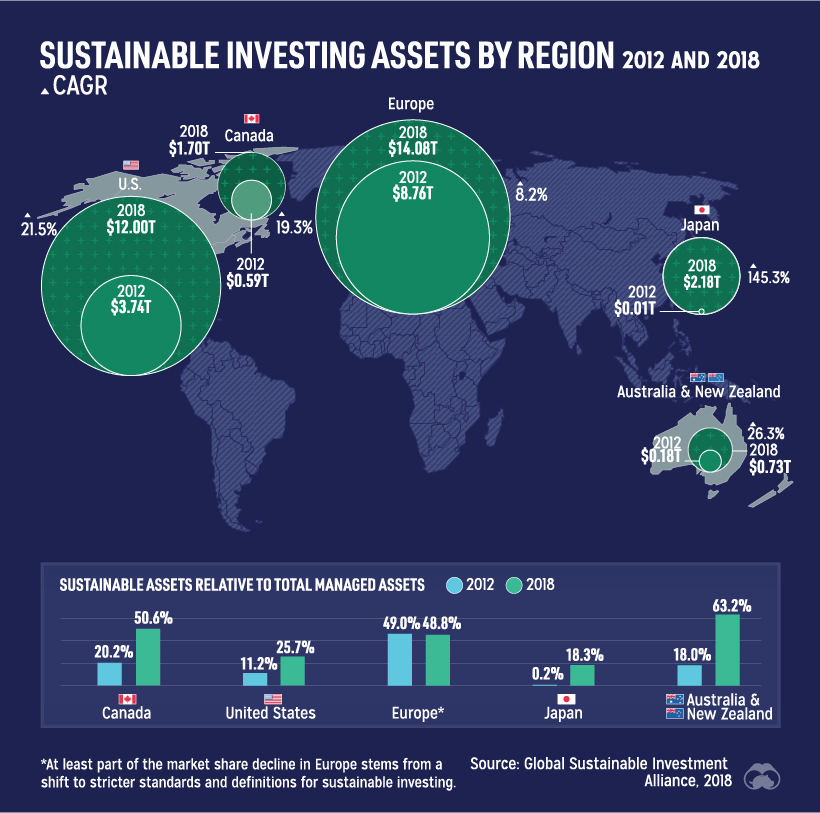

By the year 2030, it’s expected that a whopping 95% of all assets will incorporate ESG factors. While this still seems far away, it’s clear that change is already happening in the investment sphere. As you can see in the following graphic, the percentage of ESG assets has already been rising by trillions of dollars per year globally:

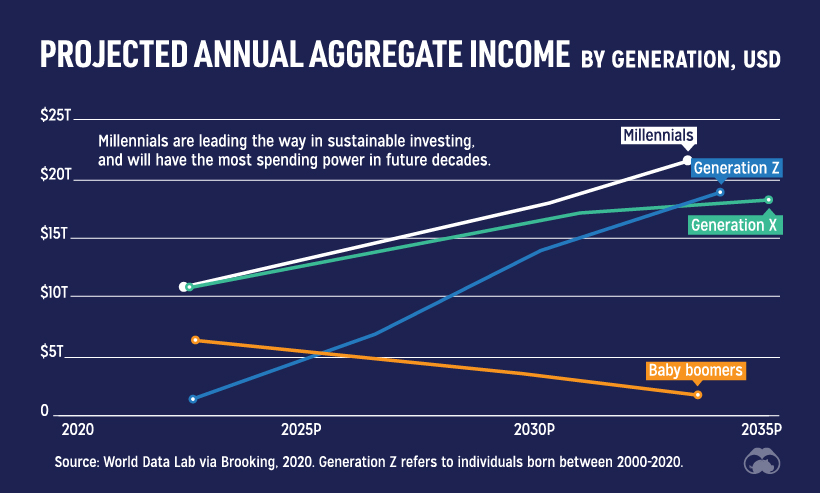

If you think this is a powerful trend now, wait until Millennials and Gen Z investors sink in their teeth. Both generations show a higher interest in sustainable investing, and both are already more likely to incorporate ESG factors into existing portfolios.

Companies are getting in front of the ESG investing trend, as well. In 2011, just 20% of companies on the S&P 500 provided sustainability reports to investors. In 2019, that percentage rose to 90%—and with the world’s biggest asset managers already on board with ESG, there’s pressure for that to hit 100% in the coming years.

#5: Stock Market Concentration

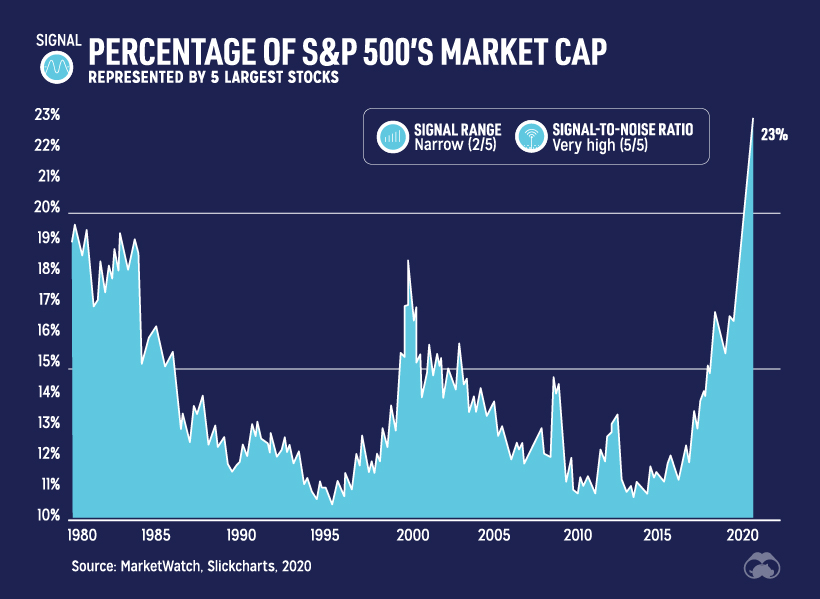

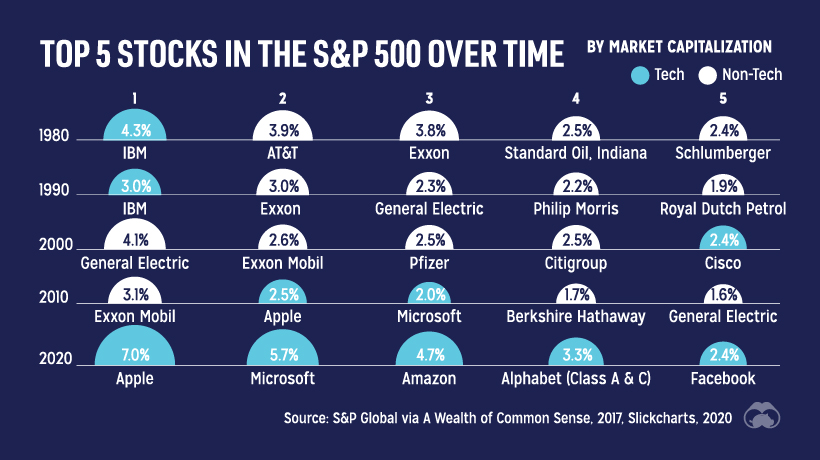

In the last 40 years, the U.S. market has never been so concentrated as it is now.

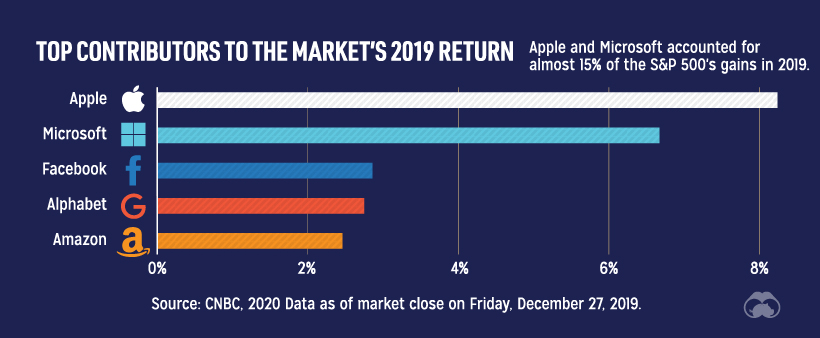

The top five stocks in the S&P 500 have historically made up less than 15% of the market capitalization of the index, but this year the percentage has skyrocketed to 23%. Not surprisingly, it’s the same companies—led by Apple and Microsoft—that propelled market performance the previous year.

Looking back at the top five companies in the S&P 500 over time helps reveal an important component of this signal, which is that it’s only a recent phenomenon for tech stocks to dominate the market so heavily.

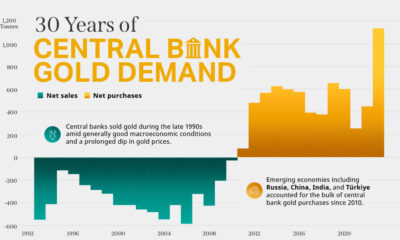

#6: Central Banks: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

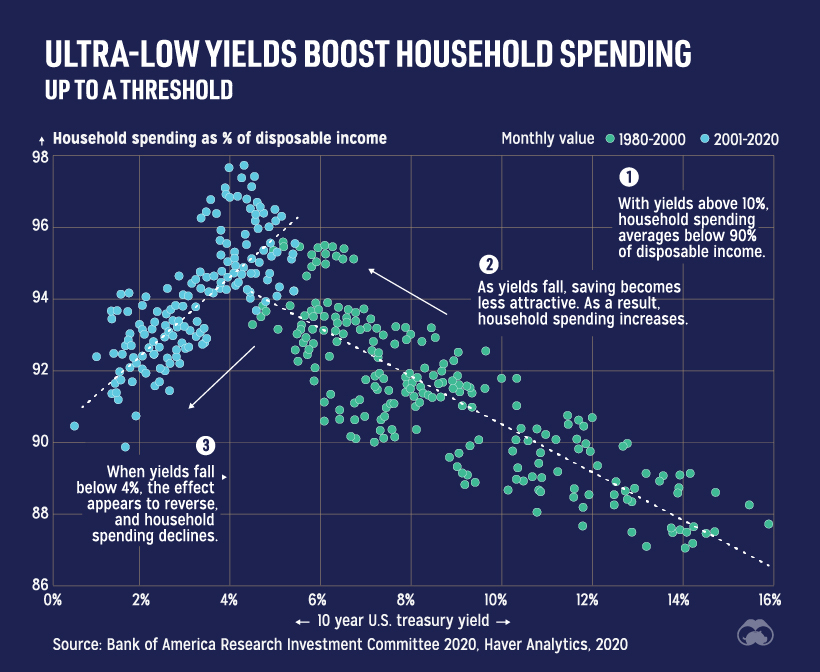

Since the financial crisis, central banks have found themselves to be in a tricky situation. As interest rates close in on the zero bound, their usual toolkit of conventional policy options has dried up. Traditionally, lowering rates has encouraged borrowing and spending to prop up the economy, but once rates get ultra-low this effect disappears or even reverses.

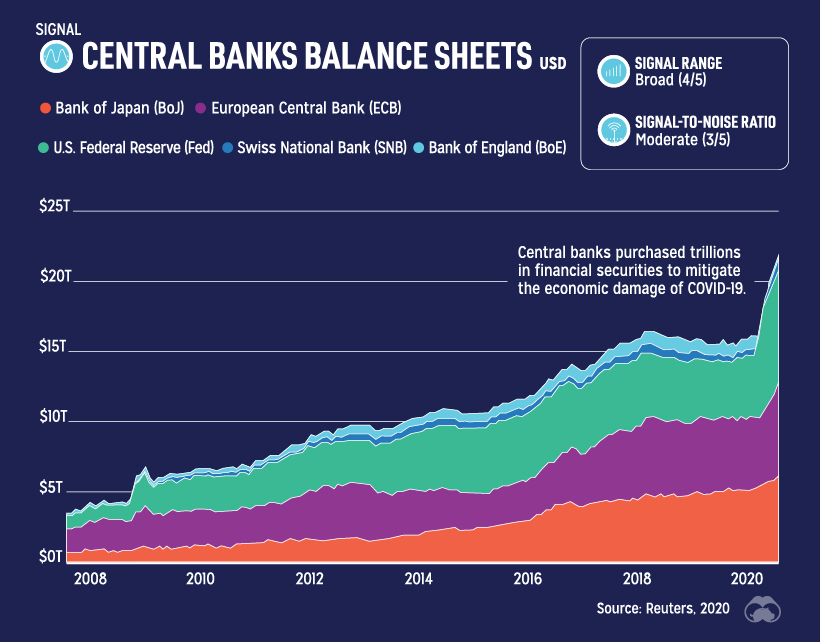

The pandemic has forced the hand of central banks to act in less conventional ways. Quantitative easing (QE)—first used extensively by the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank after the financial crisis—has now become the go-to tool for central banks. By buying long-term securities on the open market, the goal is to increase money supply and encourage lending and investment. In Japan, where QE has been a mainstay since the late-1990s, the Bank of Japan now owns 80% of ETF assets and roughly 8% of the domestic equity market.

As banks “print money” to buy more assets, their balance sheets rise concurrently. This year, the Fed has already added over $3.5 trillion to the U.S. money supply (M2) as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, and there’s still likely much more to be done. Regardless of how the monetary policy experiment turns out, it’s clear that this and many of the other aforementioned signals will be key drivers for the future of markets and investing. If you like this post, find hundreds of charts like this in our new book “Signals”:

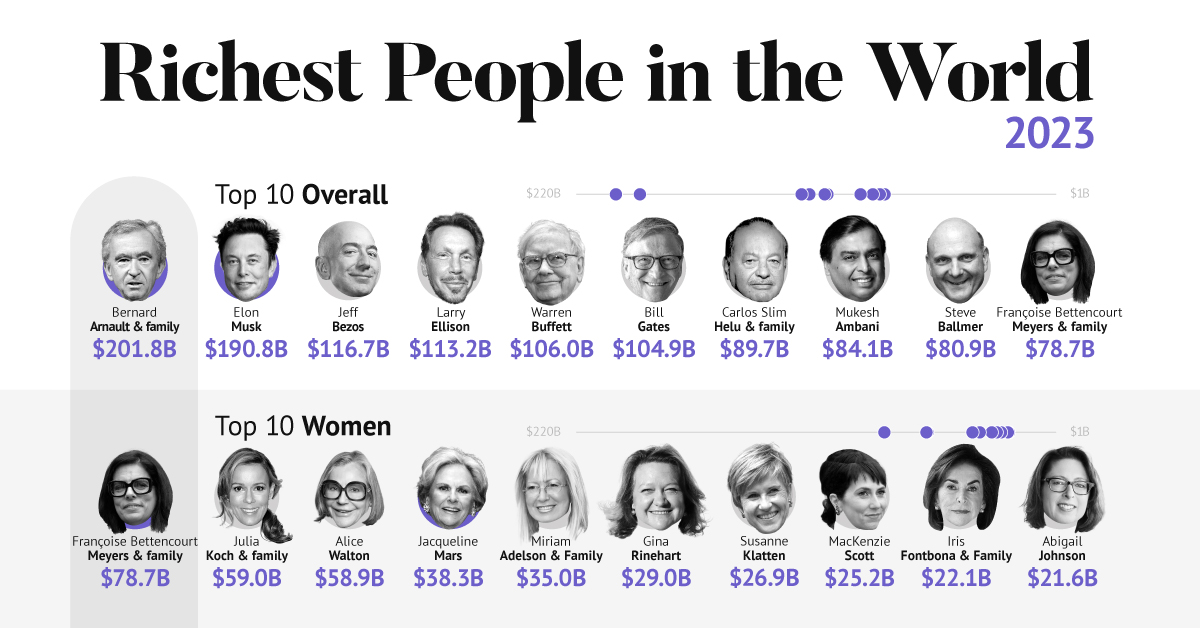

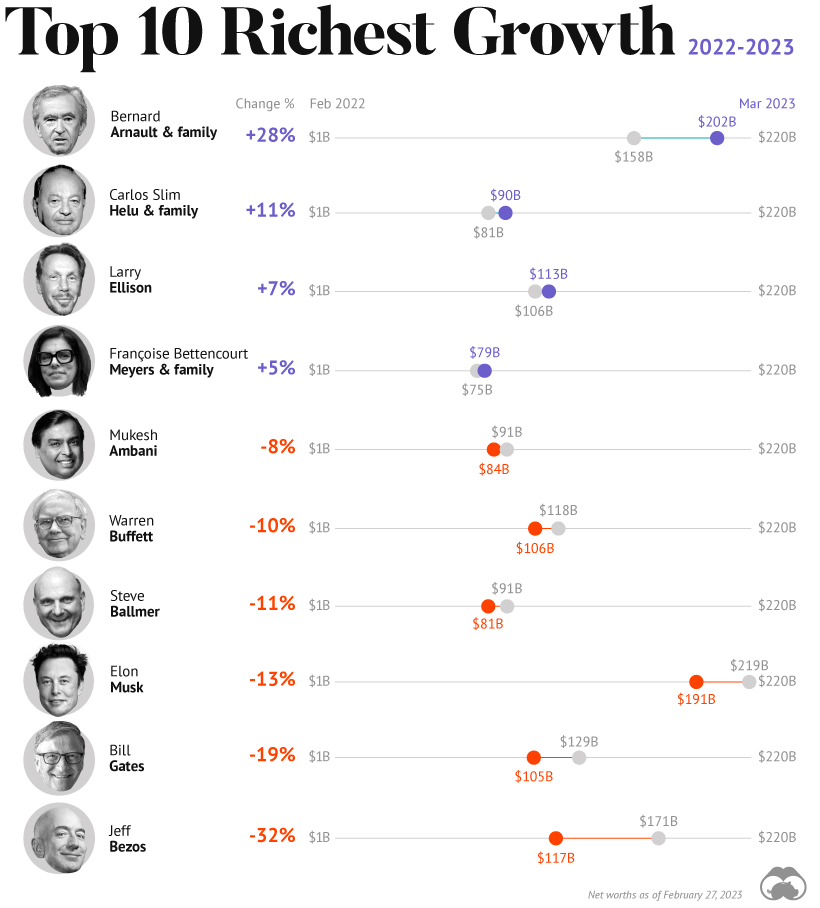

on A lagging stock market dented these fortunes against high interest rates, energy shocks, and economic uncertainty. But some of the world’s billionaires have flourished in this environment, posting sky-high revenues in spite of inflationary pressures. With data from Forbes Real-Time Billionaires List, we feature a snapshot of the richest people in the world in 2023.

Luxury Mogul Takes Top Spot

The world’s richest person is France’s Bernard Arnault, the chief executive of LVMH.

With 75 brands, the luxury conglomerate owns Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, and Tiffany. LVMH traces back to 1985, when Arnault cut his first major deal with the company by acquiring Christian Dior, a firm that was struggling with bankruptcy.

Fast-forward to today, and the company is seeing record profits despite challenging market conditions. Louis Vuitton, for instance, has doubled its sales in four years.

In the table below, we show the world’s 10 richest people with data as of February 27, 2023:

Elon Musk, the second-wealthiest person in the world has a net worth of $191 billion. In October, Musk took over Twitter in a $44 billion dollar deal, which has drawn criticism from investors. Many say it’s a distraction from Musk’s work with Tesla.

While Tesla shares have rebounded—after falling roughly 70% in 2022—Musk’s wealth still sits about 13% lower than in March of last year.

Third on the list is Jeff Bezos, followed by Larry Ellison. The latter of the two, who founded Oracle, owns 98% of the Hawaiian island of Lanai which he bought in 2012 for $300 million.

Fifth on the list is Warren Buffett. In his annual letter to shareholders, he discussed how Berkshire Hathaway reported record operating profits despite economic headwinds. The company outperformed the S&P 500 Index by about 22% in 2022.

How Fortunes Have Changed

Given multiple economic crosscurrents, billionaire wealth has diverged over the last year. Since March 2022, just four of the top 10 richest in the world have seen their wealth increase. Two of these are European magnates, while Carlos Slim Helu runs the largest telecom firm in Latin America. In fact, a decade ago Slim was the richest person on the planet. Overall, as the tech sector saw dismal returns over the year, the top 10 tech billionaires lost almost $500 billion in combined wealth.

Recent Shakeups in Asia

Perhaps the most striking news for the world’s richest centers around Gautam Adani, formerly the richest person in Asia. In January, Hindenburg Research, a short-selling firm, released a report claiming that the Adani Group engaged in stock manipulation and fraud. Specifically, the alleged the firm used offshore accounts to launder money, artificially boost share prices, and hide losses. The Adani Group, which owns India’s largest ports—along with ports in Australia, Sri Lanka, and Israel—lost $100 billion in value in the span of a few weeks. Interestingly, very few Indian mutual funds hold significant shares in Adani Group, signaling a lack of confidence across India’s market, which was also cited in Hindenburg’s report. As a result, Mukesh Ambani has climbed to Asia’s top spot, controlling a $84 billion empire that spans from oil and gas and renewable energy to telecom. His conglomerate, Reliance Industries is the largest company by market cap in India.