Since the direction of the overall economy also affects stock markets, measures of consumer sentiment have historically moved in tandem with major indices like the S&P 500. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, however, consumers and stock markets have become noticeably disjointed from one another. To help us understand why this may be the case, this infographic charts the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment against the S&P 500, before diving into potential underlying factors for their divergence.

A Tale of Two Indices

Before we compare these two indices, it’s helpful to first understand how they’re comprised.

The Index of Consumer Sentiment

The University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment (ICS) is derived from a monthly survey of consumers that aims to get a snapshot of personal finances, business conditions, and buying conditions in the market. The survey consists of five questions (paraphrased):

Are you better or worse off financially compared to a year ago? Will you be better or worse off financially a year in the future? Will business conditions during the next year be good, bad, or other? Will business conditions over the next five years be good, bad, or other? Is it a good time to make large purchases such as major household appliances?

A score for each of these questions is calculated based on the percent of favorable and nonfavorable replies. The scores are then aggregated to arrive at the final index value, relative to 6.8—the 1966 base period value.

The S&P 500

The S&P 500 is a market capitalization-weighted index of the 500 largest publicly traded U.S. companies. A company’s market capitalization is calculated as its current stock price multiplied by its total number of outstanding shares. Market caps change over time, with movements determined by daily stock price fluctuations, the issuance of new stock, or the repurchase of existing shares (also known as share buybacks).

The COVID-19 Divergence

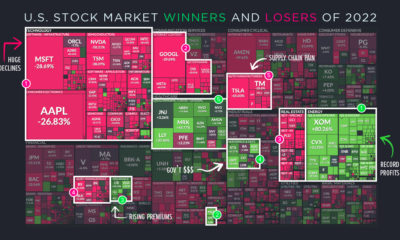

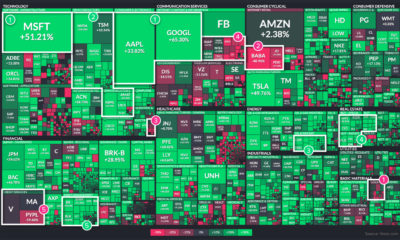

Throughout past market cycles, these two indices have displayed some degree of correlation. During the bull market of the ‘90s, the S&P 500 generated an astonishing 417% return, and was accompanied by a 75% increase in consumer sentiment. Critically, both indices also peaked at roughly the same time. The ICS began to decline after reaching its record high of 112.0 in January 2000, while the S&P 500 began to falter in August that same year. Fast forwarding to 2020, we can see that these indices have responded quite differently during the pandemic so far: All figures as of month end unless otherwise specified. Source: Yahoo Finance The ICS has not yet recovered from its initial decline beginning in March, whereas the S&P 500 has seemingly bounced back during the same time frame.

Examining the Disconnect

Why are stock markets failing to recognize the hardships that consumers are feeling? Let’s examine two central factors behind this disconnect.

Reason 1: Tech’s Dominance of the S&P 500

Recall that a company’s weight in the S&P 500 is determined by its market cap. This means that certain sectors can form a larger part of the index than others. Here’s how each sector sizes up: Source: S&P Global Based on this breakdown, we can see that the information technology (IT) sector accounts for over a quarter of the S&P 500. With a weighting of 27.5%, the sector alone is bigger than the bottom six combined (Industrials to Materials). This inequality means the performance of the IT sector has a stronger relative impact on the index’s overall returns. Within IT, we can highlight the FAANGM subset of stocks, which include some of America’s biggest names in tech: Source: Yahoo Finance These companies have grown rapidly over the past decade, and continue to perform strongly during the pandemic. If this trend continues, the S&P 500 could skew even further towards the IT sector, and become less representative of America’s overall economy.

Reason 2: The U.S. Federal Reserve

Stock prices typically reflect a company’s future earnings prospects, meaning they are influenced, to a degree, by the outlook for the broader economy. With an ongoing pandemic and steep decline in consumer sentiment, it’s reasonable to believe that many company prospects would look bleak. This is especially true for consumer cyclicals—companies like automobile manufacturers that rely on discretionary spending. In a somewhat controversial move, the U.S. Federal Reserve has stepped in to counter these effects by creating the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF). This facility operates two programs which ensure businesses have access to funding during the pandemic. Corporate Bond Purchase Program The SMCCF is currently buying corporate bonds from an index of nearly 800 companies. Of the ten largest recipients of this program, five are categorized as consumer cyclical: Source: Investopedia This program is intended to support the flow of credit, but its announcement in June also gave stock markets a boost in confidence. With the Fed directly supporting corporations, shareholders are being shielded from risks related to declining sales and bankruptcy. By the end of June, the SMCCF had purchased $429 million in corporate bonds. ETF Purchase Program The SMCCF is also authorized to purchase corporate bond ETFs, a historic first for the Fed. The facility’s five largest ETF purchases as of June 18, 2020, are detailed below: Source: Investopedia Although the SMCCF’s purchase of ETFs outsize those of corporate bonds, the Fed has signaled its intention to make direct bond purchases its primary focus going forward.

Will Markets and Consumers Reconnect Anytime Soon?

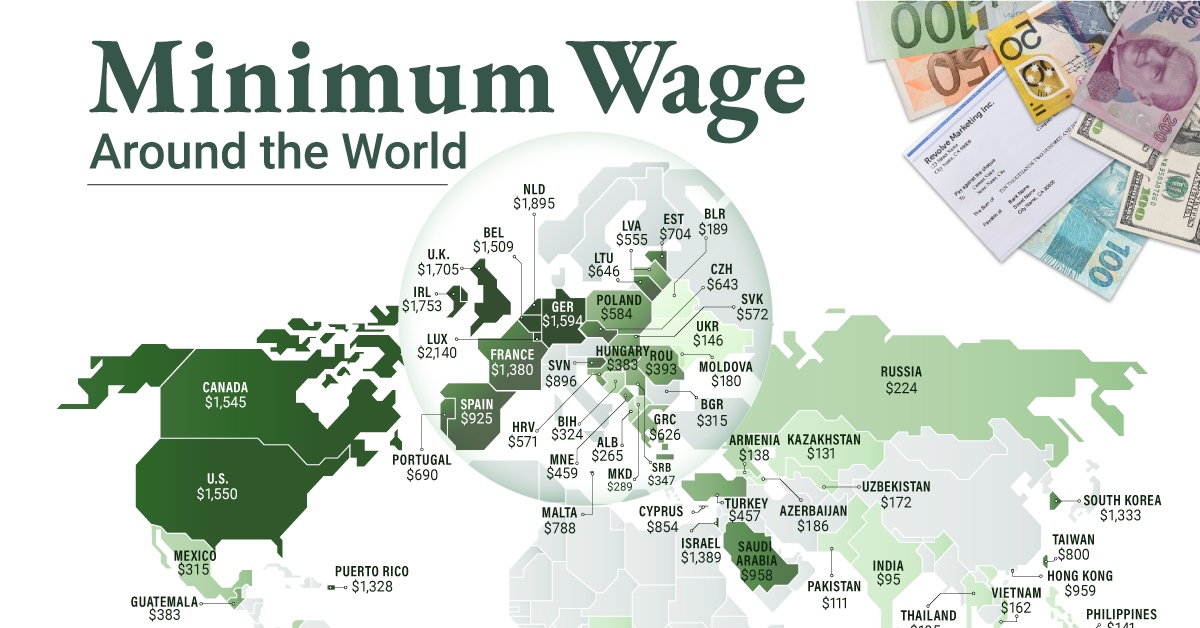

It’s hard to see the S&P 500 moving towards a more balanced sector composition in the near future. America’s big tech stocks have been resilient during the pandemic, with some even reaching new highs. The Fed also remains committed to providing corporations with credit, thereby enabling them to “borrow” their way out of the pandemic. These commitments have propped up stock markets by reducing bankruptcy risk and potentially speeding up the economic recovery. Consumer sentiment, on the other hand, has yet to show signs of recovery. Surveys released in early July may shed some light on why—63% of Americans believe it will take a year or more for the economy to fully recover, while 82% are hoping for an extension of COVID-19 relief programs. With both sides moving in opposite directions, it’s possible the disconnect could grow even larger before it starts to shrink. on To see how the minimum wage differs around the world, we’ve visualized data from Picodi, which includes values for 67 countries as of January 2023.

Monthly Minimum Wage, by Country

The following table includes all of the data used in this infographic. Each value represents the monthly minimum wage a full-time worker would receive in each country. Picodi states that these figures are net of taxes and have been converted to USD. Generally speaking, developed countries have a higher cost of living, and thus require a higher minimum wage. Two outliers in this dataset are Argentina and Turkey, which have increased their minimum wages by 100% or more from January 2022 levels. Turkey is suffering from an ongoing currency crisis, with the lira losing over 40% of its value in 2021. Prices of basic goods have increased considerably as the Turkish lira continues to plummet. In fact, a 2022 survey found that 70% of people in Turkey were struggling to pay for food. Argentina, South America’s second-biggest economy, is also suffering from very high inflation. In response, the country announced three minimum wage increases throughout 2022.

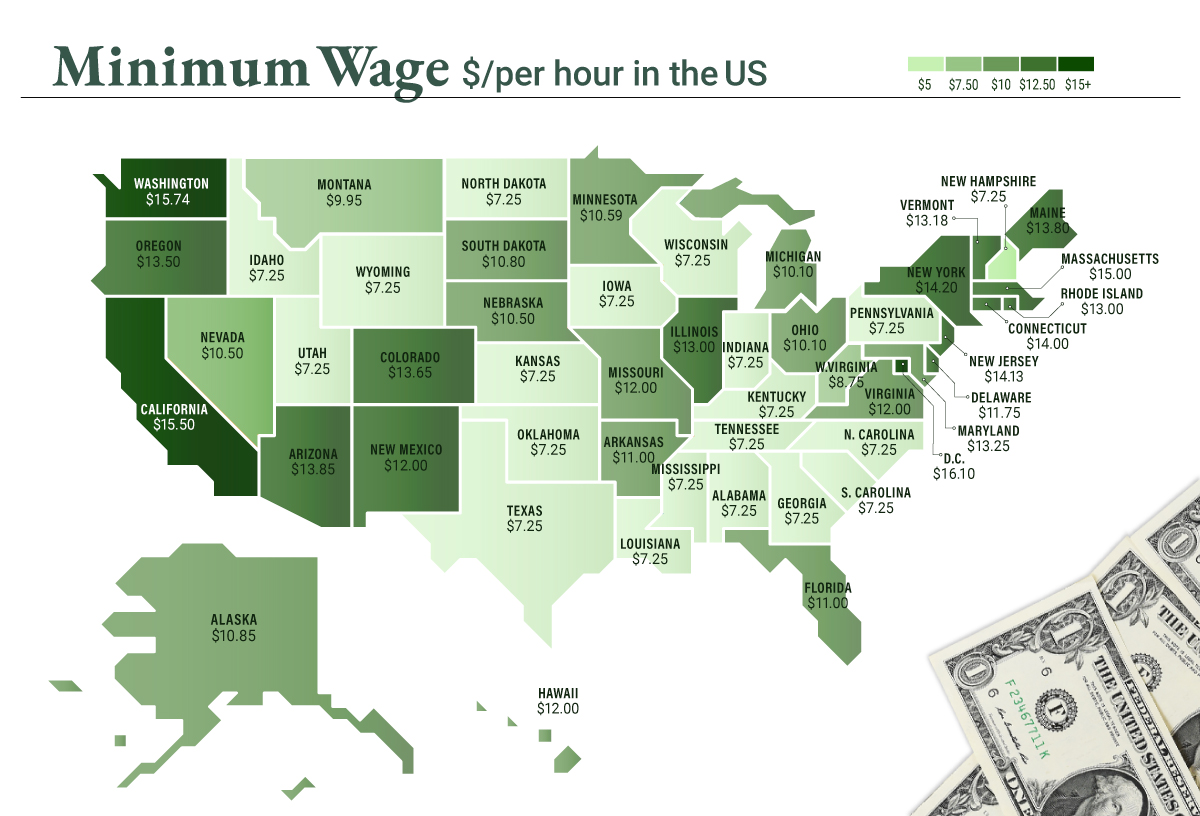

Minimum Wage in the U.S.

Within the U.S., minimum wage varies significantly by state. We’ve visualized each state’s basic minimum rate (hourly) using January 2023 data from the U.S. Department of Labor.

2023-03-17 Update: This map was updated to fix several incorrect values. We apologize for any confusion this may have caused. America’s federal minimum wage has remained unchanged since 2009 at $7.25 per hour. Each state is allowed to set their own minimum wage, as long as it’s higher than the federal minimum. In states that do not set their own minimum, the federal minimum applies. If we assume someone works 40 hours a week, the federal minimum wage of $7.25 translates to an annual figure of just $15,080 before taxes. California’s minimum wage of $15.50 translates to $32,240 before taxes. For further perspective, check out our 2022 infographic on the salary needed to buy a home across 50 U.S. cities.